Afterthoughts on the APS April meeting

Posted by David Zaslavsky on — CommentsI know, I know, it’s been far too long — almost three weeks, now — since I went to the APS April meeting in Savannah, without any update on the blog. And I did say I was going to report on interesting results that I saw there. Uh… oops!

The honest truth, though, is that not a whole lot of new stuff gets presented at the April meeting. So don’t worry that I’ve been withholding all the awesome new science I learned; I just didn’t think there was anything particularly urgent to post about.

Future of the April meeting

This is actually kind of a problem for the future of the April meeting itself. It’s a relatively small meeting, with only a few hundred attendees, and that number isn’t getting any bigger. After all, if people know not to expect groundbreaking or exciting new results to be presented at the April meeting, what’s their motivation to come?

The people in charge of the meeting know this, and they’re trying to determine what needs to be done to keep attendance up in the future. If it’s going to continue to be useful, the meeting needs to become the “hub” for some particular topic — the canonical place to present any new results in that field, as the March APS meeting is for condensed matter.

My own personal idea, which I would explain to anyone who would listen (sorry!), is that perhaps the April meeting could focus on attracting presentations in communication and education. Most fields of physics research already have their own established conferences, but as far as I know, there’s no “hub” for science communication research. The closest thing I know about is Science Online Together, but that’s not really targeted at researchers. There might be a niche for something that is. (This is not really all that plausible, I think, but hey, people wanted to hear ideas.)

Highlights

Of course, I did go to some events that, if not exactly groundbreaking, were pretty interesting.

One of the better events for me was the Tutorial for Authors and Referees and reception with the APS editors. It was a small discussion with some of the editors of the APS journals (Physical Review C, D, and Letters) targeted at grad students and early career researchers. The editors gave out lots of information on best practices for submitting a paper to get it to pass peer review (proofread, pay attention to the journal’s requirements… standard stuff), and also good advice on how to get started as a reviewer.

Toward the end, a few people pointed out the difference between the way scientists used to get access to published research in “the old days” — eagerly waiting for each issue of a printed journal to arrive in the main — and the way up-and-coming scientists get access to it in modern times, with a web search and a preprint archive, which would appear to cut journals out of the picture entirely. So what is the role of a journal in the modern scientific model? Based on what people said, it seems to center on curation of content — that is, picking out the interesting stuff and highlighting it. The new Physical Review Letters website has Editors’ Suggestions on the front page for precisely this reason: they’ve picked out some of the items with the broadest interest from all the papers they publish, so if you want to stay up to date on key developments in physics, those are the papers to be aware of.

The next day, I saw a rather surprising presentation about clickers in physics education. If you’re not familiar with them, clickers are little wireless transmitters with buttons labeled A, B, C, D, etc. In a lecture, you can put up a slide with a multiple-choice question and have students use their clicker to pick the answer, like a very quick in-class quiz, to get a sense of how well people understand what you’re teaching. They’re starting to catch on because there’s a lot of research showing that this sort of “interactive education” produces better results than traditional lecturing, but the conclusion of the presented research by Amy Shapiro, Grant O’Rielly, and Judith Sims-Knight is that clickers themselves (divorced from other interactive techniques) may not actually be doing that much good at all! They compared the results of introductory physics classes without clickers, and with clickers used on various types of material (factual and/or conceptual), and found that the control groups with no clickers uniformly had the best performance on exams, whereas using clickers to reinforce e.g. factual learning would decrease the exam performance on conceptual questions. If this result holds up, it seems that the benefits of interactive education come from other changes, not the use of clickers.

Of course I would be remiss (such a funny word, remiss) not to mention the “big” event of the APS meeting, a talk by Neil DeGrasse Tyson about his experiences on Twitter and how to use it to connect with nonscientists. Rather than summarize everything here I’ll just refer you to a Storify session of the tweets I sent during Neil’s talk. Now, if you ask me, this was kind of an oddly placed presentation. He did have a few pieces of good advice for communicating science and engaging the public — chief among them, you have to get to know what matters to your audience (nonscientists) and tailor your message to appeal to them, because they won’t go through the effort to learn to understand “scientist-speak” — but most of the time in the plenary session he spent showing off sciencey memes from Twitter and elsewhere online. Not that there’s anything wrong with that; in fact I kind of like the idea of having an entertaining presentation to relax your brain between high-level scientific talks. But I was kind of hoping for some more concrete advice about engaging people on Twitter than what we actually got.

Later that day, over lunch, Neil held a Q&A session for grad students, which was a bit more substantive. I’ve also included the tweets from that lunch discussion in the Storify. But the theme, to whatever extent there was one, was the same: when communicating science you have to make yourself understood to your audience.

Twitter connections

Speaking of Twitter: I met a surprising number of people I know from Twitter while in Savannah! You should follow them:

- Rhett Allain (@rjallain), professor of physics and physics education at Southeastern Louisiana University and science blogger for Wired

- Aatish Bhatia (@aatishb), engineering educator at Princeton University and another Wired science blogger (who I also met at Science Online 2014)

- Robert Garisto (@RobertGaristo), editor of Physical Review Letters

- Kevin Dusling (@KevinDusling), also editor of Physical Review Letters

- Sean Bartz (@excitedstate), grad student in string theory

- Christine Truong (@physicsvalkyria), aspiring nuclear physicist

- Diandra Leslie-Pelecky (@drdiandra), science communicator and author of The Physics of NASCAR

And so on…

All in all it was a busy and exhausting trip. I’ve needed the last couple weeks to relax and work on some research. I’ll try to squeeze in another blog post or two before my next trip, to Germany in mid-May for Quark Matter 2014.

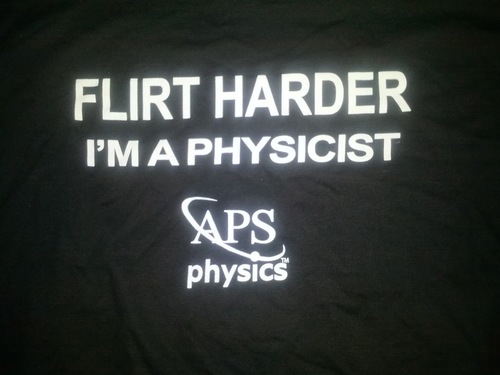

One final note: I couldn’t resist buying this corny T-shirt:

Truth.